What Was the United States First Response to the Terrorist Attacks of September 11

2 Decades Later, the Enduring Legacy of 9/11

Americans watched in horror as the terrorist attacks of Sept. eleven, 2001, left near 3,000 people expressionless in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Nearly twenty years later, they watched in sorrow as the nation's military mission in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan – which began less than a month later on 9/11 – came to a bloody and cluttered determination.

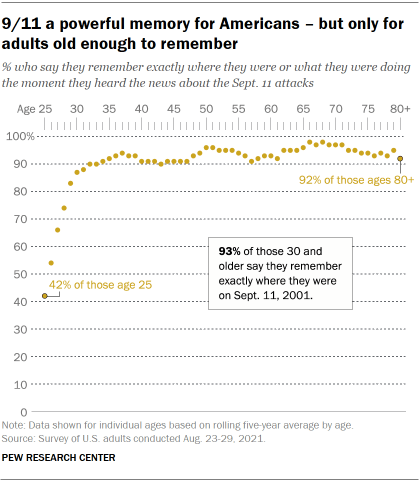

The enduring power of the Sept. 11 attacks is articulate: An overwhelming share of Americans who are one-time enough to recall the solar day remember where they were and what they were doing when they heard the news. Yet an e'er-growing number of Americans accept no personal memory of that day, either because they were likewise young or not nevertheless born.

A review of U.S. public opinion in the two decades since 9/11 reveals how a desperately shaken nation came together, briefly, in a spirit of sadness and patriotism; how the public initially rallied backside the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, though support waned over time; and how Americans viewed the threat of terrorism at home and the steps the government took to combat information technology.

Every bit the country comes to grips with the tumultuous exit of U.S. military forces from Afghanistan, the departure has raised long-term questions about U.S. foreign policy and America's identify in the world. Yet the public's initial judgments on that mission are clear: A majority endorses the decision to withdraw from Afghanistan, even as information technology criticizes the Biden administration'southward handling of the situation. And after a war that cost thousands of lives – including more than 2,000 American service members – and trillions of dollars in armed services spending, a new Pew Research Centre survey finds that 69% of U.S. adults say the United states of america has by and large failed to achieve its goals in Afghanistan.

This examination of how the Usa changed in the two decades following the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks is based on an analysis of past public opinion survey data from Pew Research Center, news reports and other sources.

Current data is from a Pew Enquiry Center survey of 10,348 U.Due south. adults conducted Aug. 23-29, 2021. Most of the interviewing was conducted before the Aug. 26 suicide bombing at Kabul airport, and all of information technology was conducted before the completion of the evacuation. Everyone who took function is a member of the Center'southward American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of pick. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population past gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, educational activity and other categories. Read more about the ATP's methodology.

Here are the questions used for the study, forth with responses, and its methodology.

A devastating emotional cost, a lasting historical legacy

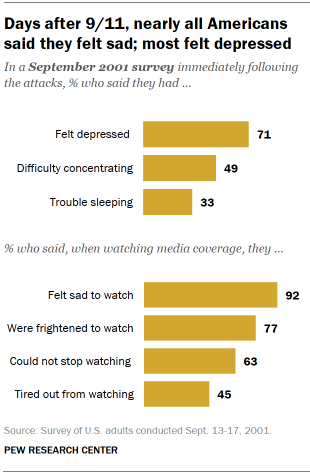

Shock, sadness, fear, acrimony: The 9/11 attacks inflicted a devastating emotional toll on Americans. But as horrible as the events of that twenty-four hour period were, a 63% majority of Americans said they couldn't end watching news coverage of the attacks.

Our get-go survey following the attacks went into the field just days after 9/11, from Sept. xiii-17, 2001. A sizable majority of adults (71%) said they felt depressed, near one-half (49%) had difficulty concentrating and a third said they had problem sleeping.

It was an era in which television was nonetheless the public'due south dominant news source – 90% said they got most of their news virtually the attacks from television, compared with just v% who got news online – and the televised images of death and devastation had a powerful impact. Effectually nine-in-x Americans (92%) agreed with the statement, "I feel distressing when watching TV coverage of the terrorist attacks." A sizable majority (77%) besides found it frightening to watch – simply most did so anyhow.

Americans were enraged by the attacks, likewise. Three weeks afterward ix/xi, fifty-fifty as the psychological stress began to ease somewhat, 87% said they felt angry about the attacks on the Earth Trade Middle and Pentagon.

Fright was widespread, not just in the days immediately after the attacks, just throughout the fall of 2001. Nearly Americans said they were very (28%) or somewhat (45%) worried most another attack. When asked a year later to depict how their lives changed in a major style, about half of adults said they felt more afraid, more than careful, more than distrustful or more than vulnerable as a upshot of the attacks.

Even after the immediate shock of 9/11 had subsided, concerns over terrorism remained at higher levels in major cities – especially New York and Washington – than in small towns and rural areas. The personal impact of the attacks likewise was felt more keenly in the cities directly targeted: Nearly a twelvemonth after nine/eleven, nearly six-in-ten adults in the New York (61%) and Washington (63%) areas said the attacks had changed their lives at least a little, compared with 49% nationwide. This sentiment was shared past residents of other large cities. A quarter of people who lived in large cities nationwide said their lives had inverse in a major style – twice the rate found in small towns and rural areas.

The impacts of the Sept. 11 attacks were securely felt and slow to misemploy. Past the post-obit August, one-half of U.S. adults said the country "had changed in a major manner" – a number that actually increased, to 61%, 10 years after the event.

A year after the attacks, in an open up-ended question, most Americans – 80% – cited nine/11 as the well-nigh of import event that had occurred in the country during the previous year. Strikingly, a larger share likewise volunteered information technology every bit the nigh important thing that happened to them personally in the prior year (38%) than mentioned other typical life events, such as births or deaths. Again, the personal touch was much greater in New York and Washington, where 51% and 44%, respectively, pointed to the attacks equally the most significant personal issue over the prior yr.

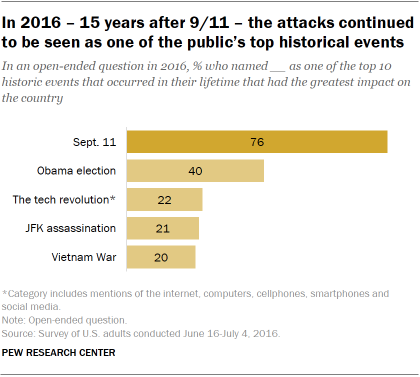

Just as memories of 9/xi are firmly embedded in the minds of most Americans quondam enough to recall the attacks, their historical importance far surpasses other events in people's lifetimes. In a survey conducted by Pew Research Eye in association with A+E Networks' HISTORY in 2016 – xv years after 9/11 – 76% of adults named the Sept. 11 attacks as ane of the x historical events of their lifetime that had the greatest impact on the country. The election of Barack Obama as the first Black president was a distant 2nd, at twoscore%.

The importance of 9/eleven transcended age, gender, geographic and even political differences. The 2016 study noted that while partisans agreed on little else that election bicycle, more than 7-in-ten Republicans and Democrats named the attacks every bit one of their peak x historic events.

ix/eleven transformed U.Southward. public opinion, but many of its impacts were brusque-lived

It is difficult to think of an effect that so profoundly transformed U.Due south. public stance across so many dimensions as the 9/xi attacks. While Americans had a shared sense of anguish subsequently Sept. eleven, the months that followed also were marked by rare spirit of public unity.

Patriotic sentiment surged in the aftermath of 9/eleven. Later on the U.Due south. and its allies launched airstrikes against Taliban and al-Qaida forces in early on October 2001, 79% of adults said they had displayed an American flag. A year later on, a 62% majority said they had often felt patriotic as a effect of the 9/11 attacks.

Moreover, the public largely fix bated political differences and rallied in back up of the nation's major institutions, as well as its political leadership. In October 2001, 60% of adults expressed trust in the federal government – a level non reached in the previous three decades, nor approached in the ii decades since then.

George Due west. Bush, who had become president nine months before afterwards a fiercely contested election, saw his task approval rise 35 percent points in the infinite of three weeks. In late September 2001, 86% of adults – including almost all Republicans (96%) and a sizable majority of Democrats (78%) – approved of the way Bush was handling his job as president.

Americans also turned to religion and faith in large numbers. In the days and weeks after nine/11, most Americans said they were praying more than often. In November 2001, 78% said organized religion's influence in American life was increasing, more than than double the share who said that eight months earlier and – similar public trust in the federal regime – the highest level in iv decades.

Public esteem rose even for some institutions that usually are not that popular with Americans. For example, in Nov 2001, news organizations received record-high ratings for professionalism. Around seven-in-10 adults (69%) said they "stand up for America," while lx% said they protected democracy.

Even so in many ways, the "nine/xi result" on public opinion was short-lived. Public trust in government, every bit well as conviction in other institutions, declined throughout the 2000s. By 2005, following another major national tragedy – the government's mishandling of the relief endeavour for victims of Hurricane Katrina – just 31% said they trusted the federal regime, half the share who said so in the months later 9/eleven. Trust has remained relatively low for the past two decades: In April of this year, only 24% said they trusted the government but almost e'er or most of the time.

Bush's approval ratings, meanwhile, never once again reached the lofty heights they did shortly after 9/eleven. By the end of his presidency, in December 2008, just 24% canonical of his chore performance.

U.S. military response: Afghanistan and Iraq

With the U.S. at present formally out of Afghanistan – and with the Taliban firmly in control of the country – most Americans (69%) say the U.South. failed in achieving its goals in Afghanistan.

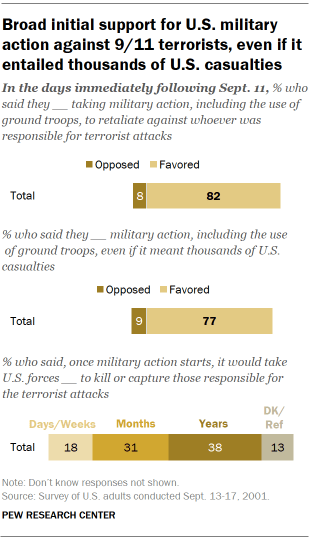

But twenty years agone, in the days and weeks following nine/11, Americans overwhelmingly supported military action confronting those responsible for the attacks. In mid-September 2001, 77% favored U.Southward. military action, including the deployment of regular army, "to retaliate against whoever is responsible for the terrorist attacks, even if that means U.S. armed forces might suffer thousands of casualties."

Many Americans were impatient for the Bush administration to give the go-alee for military machine action. In a late September 2001 survey, nearly half the public (49%) said their larger concern was that the Bush administration would not strike quickly plenty against the terrorists; but 34% said they worried the administration would motion likewise chop-chop.

Even in the early stages of the U.Due south. military machine response, few adults expected a military operation to produce quick results: 69% said it would take months or years to dismantle terrorist networks, including 38% who said information technology would take years and 31% who said information technology would have several months. Simply 18% said information technology would have days or weeks.

The public's support for armed forces intervention was evident in other ways too. Throughout the fall of 2001, more Americans said the best way to preclude future terrorism was to take military action abroad rather than build up defenses at dwelling house. In early on October 2001, 45% prioritized military machine action to destroy terrorist networks around the world, while 36% said the priority should be to build terrorism defenses at dwelling.

Initially, the public was confident that the U.S. military try to destroy terrorist networks would succeed. A sizable majority (76%) was confident in the success of this mission, with 39% proverb they were very confident.

Support for the war in Afghanistan connected at a high level for several years to come. In a survey conducted in early 2002, a few months after the start of the war, 83% of Americans said they approved of the U.S.-led war machine campaign against the Taliban and al-Qaida in Afghanistan. In 2006, several years after the United States began combat operations in Afghanistan, 69% of adults said the U.S. fabricated the right determination in using armed forces force in Afghanistan. Merely ii-in-ten said information technology was the incorrect determination.

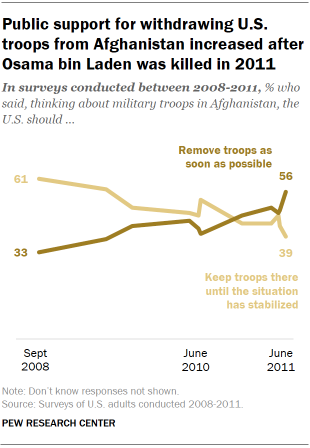

But as the conflict dragged on, first through Bush's presidency and and so through Obama'southward administration, support wavered and a growing share of Americans favored the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan. In June 2009, during Obama's showtime year in office, 38% of Americans said U.S. troops should be removed from Afghanistan as before long as possible. The share favoring a speedy troop withdrawal increased over the next few years. A turning bespeak came in May 2011, when U.Southward. Navy SEALs launched a risky operation confronting Osama bin Laden's compound in Pakistan and killed the al-Qaida leader.

The public reacted to bin Laden's death with more of a sense of relief than jubilation. A calendar month after, for the get-go time, a majority of Americans (56%) said that U.S. forces should exist brought home equally presently equally possible, while 39% favored U.South. forces in the state until the situation had stabilized.

Over the next decade, U.South. forces in Afghanistan were gradually drawn downwardly, in fits and starts, over the administrations of iii presidents – Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Meanwhile, public support for the decision to employ strength in Afghanistan, which had been widespread at the offset of the conflict, declined. Today, subsequently the tumultuous exit of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, a slim bulk of adults (54%) say the decision to withdraw troops from the land was the right decision; 42% say information technology was the wrong decision.

There was a similar trajectory in public attitudes toward a much more expansive conflict that was function of what Bush-league termed the "state of war on terror": the U.S. war in Republic of iraq. Throughout the contentious, yearlong debate before the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Americans widely supported the utilize of military machine force to end Saddam Hussein'south dominion in Iraq.

Importantly, most Americans idea – erroneously, every bit it turned out – in that location was a directly connectedness betwixt Saddam Hussein and the nine/11 attacks. In October 2002, 66% said that Saddam helped the terrorists involved in the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Eye and the Pentagon.

In April 2003, during the first month of the Republic of iraq War, 71% said the U.S. made the right conclusion to go to war in Republic of iraq. On the 15th ceremony of the war in 2018, just 43% said it was the right decision. As with the case with U.S. interest in Afghanistan, more Americans said that the U.S. had failed (53%) than succeeded (39%) in achieving its goals in Iraq.

The 'new normal': The threat of terrorism after 9/xi

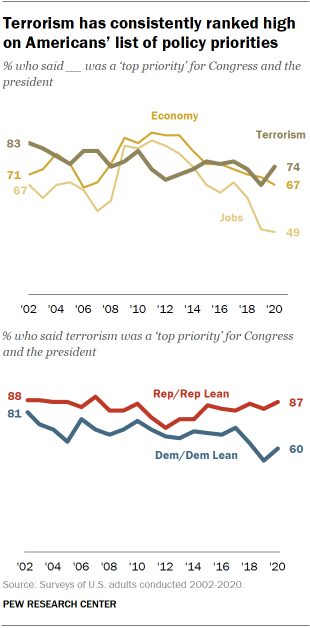

There take been no terrorist attacks on the scale of nine/11 in 2 decades, just from the public's perspective, the threat has never fully gone away. Defending the country from future terrorist attacks has been at or near the top of Pew Research Center'due south annual survey on policy priorities since 2002.

In January 2002, simply months subsequently the 2001 attacks, 83% of Americans said "defending the country from future terrorist attacks" was a superlative priority for the president and Congress, the highest for whatever outcome. Since then, sizable majorities have continued to cite that as a top policy priority.

Majorities of both Republicans and Democrats have consistently ranked terrorism as a top priority over the past 2 decades, with some exceptions. Republicans and Republican-leaning independents have remained more likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners to say defending the country from future attacks should exist a top priority. In recent years, the partisan gap has grown larger as Democrats began to rank the event lower relative to other domestic concerns.

The public's concerns nearly some other attack as well remained fairly steady in the years after 9/11, through virtually-misses and the federal regime'due south numerous "Orange Alerts" – the second-almost serious threat level on its color-coded terrorism warning system.

A 2010 analysis of the public's terrorism concerns constitute that the share of Americans who said they were very concerned about another assault had ranged from about 15% to roughly 25% since 2002. The merely time when concerns were elevated was in Feb 2003, before long before the start of the U.S. war in Republic of iraq.

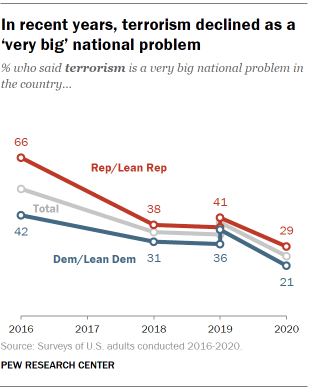

In recent years, the share of Americans who point to terrorism as a major national problem has declined sharply as problems such equally the economy, the COVID-19 pandemic and racism take emerged as more than pressing issues in the public's eyes.

In 2016, well-nigh half of the public (53%) said terrorism was a very large national problem in the land. This declined to about iv-in-ten from 2017 to 2019. Last yr, merely a quarter of Americans said that terrorism was a very big problem.

This twelvemonth, prior to the U.South. withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan and the subsequent Taliban takeover of the country, a somewhat larger share of adults said domestic terrorism was a very big national problem (35%) than said the same about international terrorism. But much larger shares cited concerns such every bit the affordability of wellness intendance (56%) and the federal budget deficit (49%) equally major problems than said that about either domestic or international terrorism.

Still, recent events in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan heighten the possibility that opinion could be irresolute, at least in the curt term. In a late August survey, 89% of Americans said the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan was a threat to the security of the U.South., including 46% who said it was a major threat.

Addressing the threat of terrorism at dwelling and abroad

Simply equally Americans largely endorsed the employ of U.S. war machine strength equally a response to the 9/11 attacks, they were initially open to a multifariousness of other far-reaching measures to combat terrorism at home and abroad. In the days following the set on, for example, majorities favored a requirement that all citizens carry national ID cards, allowing the CIA to contract with criminals in pursuing suspected terrorists and permitting the CIA to conduct assassinations overseas when pursuing suspected terrorists.

However, near people drew the line against allowing the authorities to monitor their own emails and phone calls (77% opposed this). And while 29% supported the establishment of internment camps for legal immigrants from unfriendly countries during times of tension or crunch – along the lines of those in which thousands of Japanese American citizens were bars during World War II – 57% opposed such a measure out.

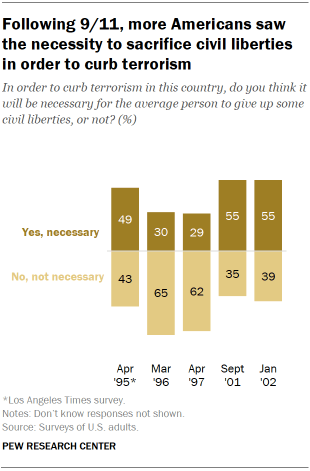

It was articulate that from the public's perspective, the balance between protecting civil liberties and protecting the country from terrorism had shifted. In September 2001 and January 2002, 55% majorities said that, in order to curb terrorism in the U.Southward., information technology was necessary for the boilerplate citizen to surrender some civil liberties. In 1997, merely 29% said this would exist necessary while 62% said it would not.

For most of the next two decades, more Americans said their bigger concern was that the government had non gone far enough in protecting the country from terrorism than said information technology went too far in restricting ceremonious liberties.

The public also did not dominion out the use of torture to extract information from terrorist suspects. In a 2015 survey of forty nations, the U.S. was one of just 12 where a majority of the public said the apply of torture against terrorists could be justified to gain information about a possible assail.

Views of Muslims, Islam grew more partisan in years later on ix/eleven

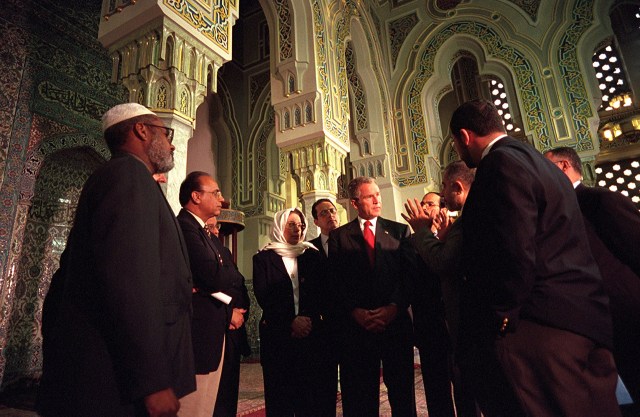

Concerned most a possible backlash against Muslims in the U.S. in the days later nine/eleven, then-President George W. Bush gave a spoken language to the Islamic Center in Washington, D.C., in which he alleged: "Islam is peace." For a cursory period, a big segment of Americans agreed. In Nov 2001, 59% of U.S. adults had a favorable view of Muslim Americans, up from 45% in March 2001, with comparable majorities of Democrats and Republicans expressing a favorable opinion.

This spirit of unity and comity was not to last. In a September 2001 survey, 28% of adults said they had grown more than suspicious of people of Middle Eastern descent; that grew to 36% less than a twelvemonth later on.

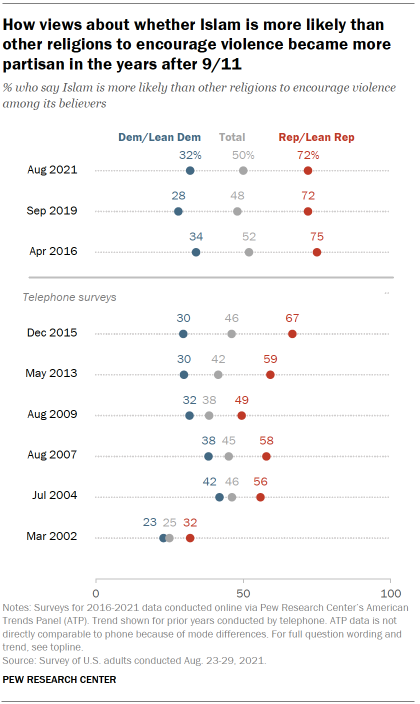

Republicans, in detail, increasingly came to associate Muslims and Islam with violence. In 2002, just a quarter of Americans – including 32% of Republicans and 23% of Democrats – said Islam was more than probable than other religions to encourage violence among its believers. About twice as many (51%) said it was not.

But inside the next few years, well-nigh Republicans and GOP leaners said Islam was more likely than other religions to encourage violence. Today, 72% of Republicans express this view, according to an August 2021 survey.

Democrats consistently take been far less likely than Republicans to acquaintance Islam with violence. In the Center's latest survey, 32% of Democrats say this. Even so, Democrats are somewhat more than likely to say this today than they have been in recent years: In 2019, 28% of Democrats said Islam was more likely than other religions to encourage violence among its believers than other religions.

The partisan gap in views of Muslims and Islam in the U.S. is evident in other meaningful ways. For example, a 2017 survey found that half of U.S. adults said that "Islam is not function of mainstream American society" – a view held by nigh seven-in-ten Republicans (68%) but just 37% of Democrats. In a carve up survey conducted in 2017, 56% of Republicans said in that location was a dandy deal or fair corporeality of extremism among U.South. Muslims, with fewer than one-half as many Democrats (22%) saying the same.

The ascension of anti-Muslim sentiment in the aftermath of nine/11 has had a profound outcome on the growing number of Muslims living in the United States. Surveys of U.S. Muslims from 2007-2017 institute increasing shares saying they have personally experienced discrimination and received public expression of support.

It has now been ii decades since the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre and Pentagon and the crash of Flight 93 – where only the courage of passengers and crew possibly prevented an even deadlier terror attack.

For most who are old enough to recollect, it is a solar day that is impossible to forget. In many means, 9/xi reshaped how Americans think of state of war and peace, their own personal rubber and their fellow citizens. And today, the violence and anarchy in a country one-half a world away brings with it the opening of an uncertain new chapter in the post-ix/11 era.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/09/02/two-decades-later-the-enduring-legacy-of-9-11/

0 Response to "What Was the United States First Response to the Terrorist Attacks of September 11"

Enregistrer un commentaire